Arkansas Stories Debuts ‘The Nelson Hackett Project’; Research Spotlight Gives In-Depth Look at His Legacy

Main image from the new website for The Nelson Hackett Project. No images of Nelson Hackett himself are known to exist.

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. – The University of Arkansas Humanities Center’s public series, Arkansas Stories of Place and Belonging, continues this fall with an exploration of The Nelson Hackett Project.

Join a team of historical experts at 7 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 28, to learn more about Nelson Hackett, an enslaved man whose 1841 flight from Fayetteville to Canada set off a chain of events that helped ensure that Canada remained a safe refuge for fugitives from American slavery.

The discussion will take place via Zoom, and participants can receive registration information by emailing NelsonHackettProject@gmail.com.

The Oct. 28 program, co-sponsored by the Washington County Historical Society, will consist of three 20-minute presentations and the official launch of a new public humanities website devoted to telling Hackett’s story.

The discussion will be hosted by Kathryn Sloan, professor of Latin American history, vice provost for faculty affairs, and director of the Arkansas Stories series. The presentations will feature scholars, including:

- Michael Pierce, associate professor of history, who created the project and will narrate Hackett’s journey to Canada, his forced return to Arkansas, and the diplomatic battles it provoked.

- Lisa Childs, a graduate student in history and the Division of Agriculture’s patent attorney, who will examine the white slaveholding community in early Fayetteville.

- Caree Banton, associate professor of history, who will conclude with a look at the role that fugitives like Hackett played in the transnational movement for emancipation and abolition.

After the discussion, the team will also officially launch the new website for The Nelson Hackett Project, which can be found on the Arkansas Stories website.

Now, get an exclusive in-depth look at the project with researcher and scholar Michael Pierce, in his own words in this spotlight story:

Research Spotlight: The Legacy of Nelson Hackett

By Michael Pierce

In the summer of 1841, Nelson Hackett, an enslaved man, fled Arkansas in search of freedom. His flight took him nearly 1000 miles, from Fayetteville across Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana, through parts of Ohio and Michigan, into Canada, and ending at Chatham, some fifty miles east of Detroit.

Upon setting foot in Canada, Hackett believed that “the humanity of the British law made him a free man.”

But Hackett would not be free for very long.

Alfred Wallace, the man who the state of Arkansas considered to be Hackett’s owner, tracked him to Chatham, had him arrested on charges of theft – Hackett had taken a horse, saddle, beaver coat, and gold watch for his flight – and secured his extradition back to Arkansas.

Hackett was the first fugitive that Canada returned to bondage. But Hackett would also be the last such fugitive that Canada sent back.

Abolitionists in North America and the United Kingdom refused to allow his return to set a precedent. Fearful that slave owners would fabricate claims of theft to extradite fugitives, they invoked Hackett’s case as they met with British and U.S. diplomats, took to the floor of the Canadian Assembly, lobbied imperial officials, and petitioned Parliament.

In the end, abolitionists secured a commitment from the British to regulate the extradition process in ways that made it nearly impossible for slavers to secure the return of fugitives.

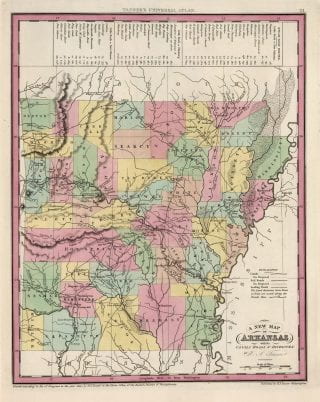

“A New Map of Arkansas with Its Canals, Roads & Distances,” (Philadelphia: H. S. Tanner, 1842). Image courtesy of the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Stanford University, davidrumsey.com

Thus, Nelson Hackett and his flight helped ensure that Canada remained a refuge for those fleeing American slavery.

The Nelson Hackett Project, a public humanities program of the University of Arkansas Humanities Center, provides a narrative of Hackett’s flight and the conflicts over extradition it provoked as well as primary documents, transcripts, maps, and images.

The purpose is not simply to honor one man’s struggle for freedom but also to demonstrate the power of human agency.

By refusing to accept the fate that slavers sought to impose upon him, Hackett transformed his own world and set in motion a transnational network of black and white abolitionists who ensured that Canada remained the promised land for those fleeing American slavery.

Hackett’s flight, thus, helped make it possible for thousands of others to flee bondage, actions that provoked slavers and fueled the sectional crisis that ended with civil war and emancipation.

One of the primary problems in reconstructing the life and flight of Nelson Hackett is that there are few records of his words and thoughts. This problem is rooted in the racism that undergirded the slave system and created most of its archival records.

Hackett’s flight is therefore reconstructed using other voices, including slavers and their apologists, black and white abolitionists, journalists, and colonial and elected officials.

This process, though, makes Hackett into someone who is acted upon and judged rather than the center of his own story and in this way obscures much of his humanity.

Only Hackett’s actions themselves – his flight from Arkansas, journey to Canada, and escape upon his return to Fayetteville – tell us about his motivations and desires.

Little is known about Hackett’s early life. He did not enter the historical record until two weeks after his escape. At that time, Alfred Wallace, a merchant and landowner, registered two bills of sale at the Washington County Courthouse.

In the first, dated June 15, 1840, Jacob Cartwright conveyed “a certain Negro Boy named Nelson about 24 years of age” to Willis Wallace in exchange for “a boy named Moses and a grey mule.” In the second, dated one day later, Willis Wallace sold “Nelson” to his brother Alfred for $1,000.

The bills of sale do not indicate how Cartwright came to own Hackett or how Hackett got to Fayetteville, which was not established until 1828. They do suggest, though, that the town’s white people knew him simply as “Nelson.” When and why he adopted the last name of Hackett, which he used in Canada, remain unknown.

The only descriptions of Hackett’s physical appearance come from an account of his return to Fayetteville. A reporter for the Peoria Register described him as “handsomely formed, about 30 years old, of very prepossessing address” and noted that he “wore his hair nicely combed, was genteelly clad, and was in short a negro dandy.”

There are conflicting accounts of Hackett’s July 1841 departure from Arkansas.

Alfred Wallace accused Hackett of leaving Fayetteville while Wallace was away and of stealing a racehorse, saddle, coat, 100 £ ($500) in silver and gold coin, and a neighbor’s watch on the way out of town. Wallace initially suggested that Hackett raped a white woman before leaving town but quickly dropped the claim.

Abolitionists, though, portrayed the thefts as incidental to Hackett’s escape. According to Charles Stewart, a white abolitionist who interviewed the fugitive in Detroit, Hackett had accompanied Wallace to a horse race “a considerable distance” from Fayetteville. Wallace did not return home but directed Hackett to take the horse and other items back.

Instead of heading to Fayetteville, Hackett made his escape. Stewart wrote, “Hackett finding himself well mounted, under circumstances that permitted absence, directed his course towards liberty … At the time he had in care the outside coat of his master, and he also had his gold watch.”

After fleeing Arkansas, Hackett headed 360 miles northeast to Marion City, Missouri, a hotbed of abolitionist activity located on the Mississippi River.

According to the account by the Peoria journalist, “[Hackett] travelled only at night, and hiding through the day in the woods, subsisting on such fare as the desert afforded. Upon reaching the [Missouri] river, he luckily found the ferry tended by a negro, of whom it is believed he made a confidant, as the same negro subsequently denied all knowledge of the fugitive’s passing that way. The friend thus gained, doubtless furnished him with a supply of food, while by his advice he was probably enabled to proceed more boldly. Avoiding the thoroughfares, he made for Marion city on the Mississippi.”

After crossing the Mississippi River, Hackett probably made his way to nearby Quincy, Illinois, a prominent starting-off point on the Underground Railroad.

The only account that describes his journey from Illinois to Chatham – the one in the Peoria Register – provides only superficial information: “Here he [Hackett] breathed freer, and ventured to pursue his journey in the day time. …As he journeyed, he would sometimes represent himself as being a free man, living in some county before him, and at others, when he thought it would better answer his purpose, as a slave escaping from bondage.”

Crossing into Canada in late August 1841, Hackett thought that he had found freedom. Alfred Wallace, though, had put a man on his trail and, after finding Hackett’s destination, personally travelled to Canada.

Wallace found Hackett in Chatham on September 6, beat him, and had him imprisoned. Wallace’s demand for Hackett’s extradition on charges of theft set off international furor.

Abolitionists – both black and white – called on Canadian authorities to honor the British Empire’s commitment to providing refuge for fugitives and grant Hackett his freedom. Defenders of slavery, and those who wanted to prevent black fugitives from settling in Canada, countered that Hackett was not simply a fugitive but also a thief who needed to be punished.

Confident that Hackett would be released, abolitionists were surprised when Canada’s governor-general, Sir Charles Bagot, ordered the fugitive to be returned to Arkansas.

Bagot explained, “to refuse to surrender him would be to establish as a principle that no slave escaping to this province should be given up, whatever offence, short perhaps of murder, he might have committed; a principle which would have been repugnant to the common sense of justice of the civilised world, would have involved us in disputes of the most inconvenient nature with the neighbouring states, and would have converted this province into an asylum for the worst characters.”

After Bagot’s February 1842 order, an agent of Arkansas’s governor transported a bound and gagged Hackett to Detroit’s jail to await a return to Fayetteville later that spring. At this time, the city’s black community mobilized the transnational abolitionist movement in an ill-fated effort to prevent Hackett’s return to Arkansas.

The Colored Vigilant Committee explained, “Hackett was not demanded by the Executive of Arkansas, for the purpose of punishing for larceny, but to punish and make an example of him for the unpardonable offense of absconding from slavery” and warned that, if the extradition was allowed to stand, Canada would “no longer be a safe asylum for our unfortunate brethren who are fleeing from bondage.”

In early May 1842, two agents of the state of Arkansas fitted Hackett with chains and a hobble for his forced return to Fayetteville. The trip began aboard a Great Lakes steamship that took them to Chicago. There, they boarded a stagecoach for a four-day trip to Peoria, where they intended to catch a steamboat.

But on the third night, while in the town of Princeton, Hackett escaped again, this time for two nights before being recaptured by an area farmer. After retrieving Hackett, the three men steamed to St. Louis before continuing on to Fayetteville.

The most detailed account of Nelson Hackett’s June 1842 return to Fayetteville appeared nine years later in the Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper. It came from William Murdock, an enslaved man who also escaped from Alfred Wallace and made his way to Canada.

Murdock recounted: “Nelson Hackett was brought back by [Alfred] Wallace … he was kept in handcuffs and fetters for some time, and closely watched besides – that he was flogged with great severity five or six times, and then sold off to the interior of Texas – that the first whipping, which was done in the presence of all the slaves, consisted of 150 lashes upon his naked body. His whippings afterward varied from 39 to 50 to 60.”

Murdock’s account is consistent with what one of Arkansas’s U.S. senators told abolitionist Lewis Tappan in late 1842: “N. H. was taken to Arkansas – tried for stealing & publickly whipped – then delivered to his master by whom was sold to some one in Texas.”

While still in Fayetteville or on his way to Texas, Hackett escaped yet again.

This is known because Arkansas’s congressman Edward Cross visited abolitionist Joshua Leavitt, an associate of Tappan, to tell him. Leavitt recounted the conversation in a letter that appeared in several abolitionist papers: Hackett “escaped a third time, and has not been heard from since; and whether he has gone clear, or is destroyed, is not known.”

Hackett’s fate will ultimately remain unknown unless additional evidence surfaces.

But his story would set off a chain of events that helped ensure that Canada remained a safe refuge for fugitives from American slavery.

Abolitionists – both in the United States and the British Empire – refused to let Hackett’s extradition set a precedent. Soon after Hackett was sold off to Texas in the late summer of 1842, U.S. secretary of state Daniel Webster and British diplomat Lord Ashburton negotiated a treaty to smooth relations between the United States and British North America.

Among the issues they addressed were land disputes, Great Lakes navigation, and the extradition of criminals. Abolitionists were especially concerned with Article 10 of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty as it codified the procedures used to extradite Hackett back to Arkansas. They feared Article 10 would not only discourage enslaved people from fleeing to Canada but also make it possible for slavers to extradite the thousands of fugitives who had already settled north of the border.

Much of the abolitionist campaign to convince the British government to revoke or modify Article 10 was built around Nelson Hackett’s extradition and the violence he endured upon his return to Fayetteville. They insisted that the injustices suffered by Hackett would be repeated thousands of times if the extradition provision was allowed to stand.

The campaign began in September 1842, when a delegation from the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society visited Lord Ashburton. Led by Lewis Tappan and Gerrit Smith, the delegation opened the meeting by discussing the “particulars of the case of Nelson Hackett.”

Lord Ashburton responded that Article 10 was needed to prevent the escape of common criminals across the border, a problem that was creating difficulties on both sides. He explained that, if fugitives from slavery had been exempted from Article 10, the U.S. Senate would reject the entire treaty. Lord Ashburton assured Tappan and Smith that the British government remained committed to abolition and “friends of the slave in England would be very watchful to see that no wrong practice took place under article ten.”

Ashburton’s assurances satisfied some, with the Boston-based Emancipator and Free American insisting that “such cases [as Hackett’s] will never pass again under the tenth article.” The Americans, though, realized that British subjects were better positioned to lobby Her Majesty’s government.

When Parliament took up ratification of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, British and Canadian abolitionists likewise invoked Hackett in demanding modification of Article 10.

Thomas Clarkson warned that the unmodified treaty threatened the security of some 12,000 Canadians who had escaped bondage in America: “slave owners, encouraged by the case of Nelson Hackett … will pester our government in Canada with thousands of applications.”

Charles Stuart insisted that the fugitives Canada would send back under Article 10 could never receive fair trials and offered Hackett’s example as proof: “Alas! He is in Arkansas – he is in the fangs of tyrants.”

Prime Minister Robert Peel’s Parliamentary majority blocked efforts to modify Article 10, fearing that the Americans would reject the amended treaty, but the pressure forced it to provide assurances that the use of Article 10 to extradite fugitives from slavery would be strictly limited.

The Colonial Office followed through by issuing very detailed instructions concerning the return of slavery’s fugitives under Article 10. The purpose was to permit extradition only in extraordinary cases, such as those involving pre-mediated murder.

Such instructions allowed Britain to maintain its treaty obligations with the United States, ensure that fugitives were treated with justice, and mollify abolitionists.

When in early 1843 officials in the Bahamas refused to extradite a Florida fugitive who had killed his master during the escape, abolitionists throughout the North Atlantic world celebrated the limits they had forced upon Article 10. Joshua Leavitt exclaimed, “The excitement, the debates, the doings in Parliament, have done much to awaken public attention that the slaveholders will not likely make application in that quarter.”

At the center of these debates was Nelson Hackett.

One man’s simple act of fleeing Arkansas and slavery set in motion events that helped to ensure that Canada and the Bahamas would remain places of asylum for those escaping bondage in America.

No fugitives after Hackett would be returned to the United States and slavery.

Although Hackett’s fate remains unknown, his martyrdom became an effective tool for those fighting to protect slavery’s fugitives.

Hackett’s legacy is, thus, significant. The persistent stream of fugitives to Canada after 1843 became one of the two principal factors (the other being the status of slavery in the western territories) that fueled the sectional crisis that led to civil war and emancipation.